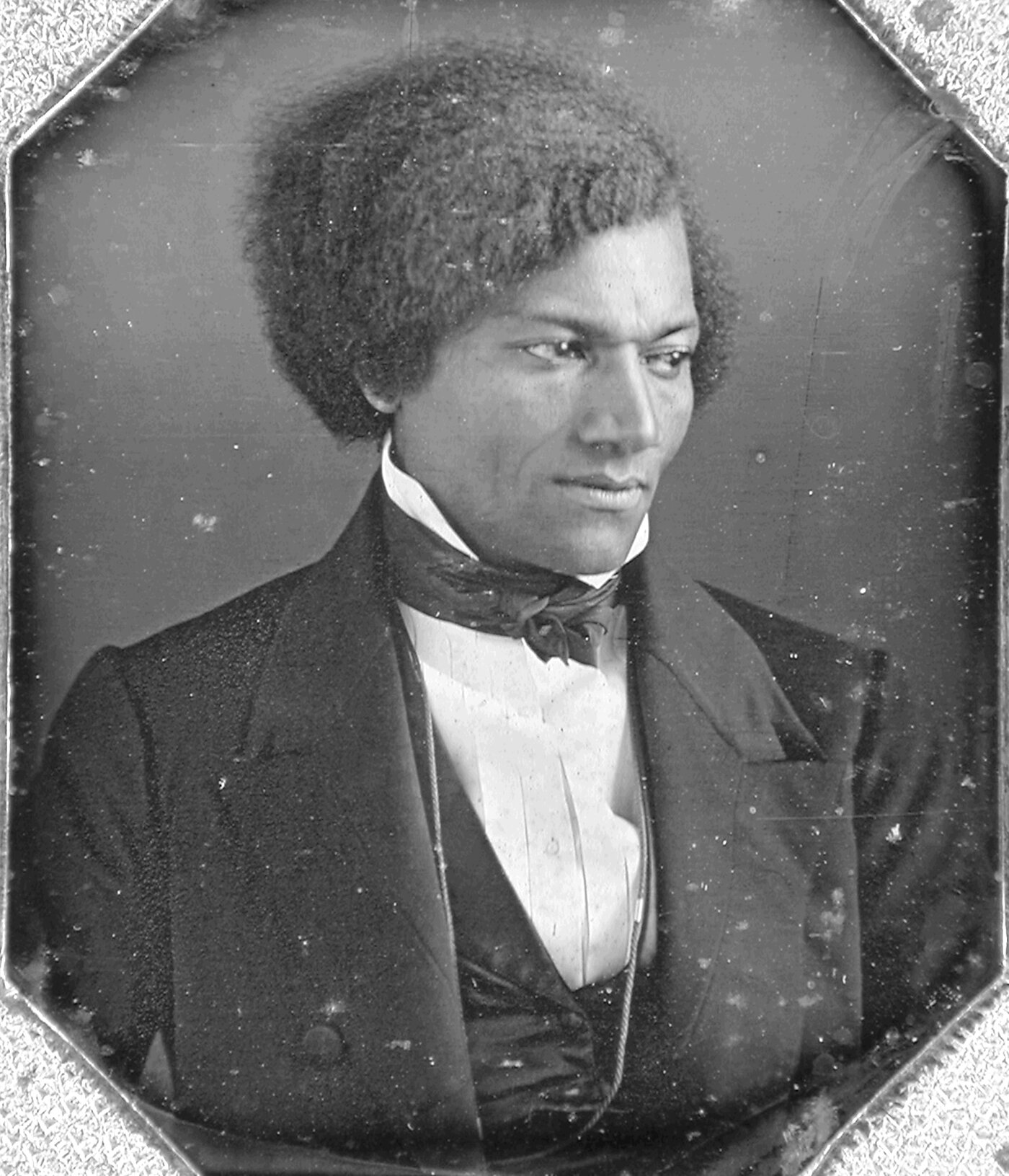

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born enslaved in Maryland, escaped, and rose to become a journalist, author, orator, diplomat, bank president, and civil rights leader. A self-made man, he championed the Declaration of Independence’s promise that all men are born free and equal. Unlike many critics, he argued the Constitution was fundamentally anti-slavery—a view explored by Cato Adjunct Scholar Timothy Sandefur in Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man, excerpted below.

… Thus, Douglass arrived back on home soil in the spring of 1847, a celebrity and rather well off. British supporters had raised enough money to help him take the next step in his career: establishing his own newspaper. When he broached the idea, the Garrisonians objected. The Liberator, they said, was enough. Douglass yielded to their judgment at first, but toward the end of the year, he changed his mind: he would proceed with the project after all. Moving to Rochester, New York, he began publishing The North Star in December. Where Garrison printed his motto, “No union with slaveholders” on the masthead, Douglass printed, “Right is of no sex—truth is of no color—God is the father of us all, and all we are brethren,” and later simply, “All rights for all.”

Close to the Canadian border, Douglass’s Rochester home became a stop on the Underground Railroad, and his family aided in the escape of perhaps 400 runaways during their time there. Rochester was also much closer to the headquarters of the Gerrit Smith wing of anti-slavery than was his old home in Garrison’s Massachusetts, and he soon began devoting columns in his paper to debates with the pro-Constitution abolitionists. Ultimately, it was Douglass who was persuaded.

In May 1851, he announced his conversion: the Constitution, he now believed, was an antislavery document, and abolitionists should vote, run for office, and use politics to fight for their cause. Disgusted by this apparent sellout, the Garrisonians claimed Douglass’s change of mind was influenced by Smith’s subsidies to The North Star—soon renamed Frederick Douglass’ Paper. But there is no reason to believe the change was anything but sincere. Douglass was never afraid to differ respectfully but openly with his allies.

Smith and other anti-slavery constitutionalists began with the premise that the Constitution must be interpreted strictly in terms of its language, rather than the Founding Fathers’ subjective intentions. What the Constitution’s authors meant is not the law; what the Constitution actually says is. Thus, when the Constitution refers to “We the People of the United States,” the word “people” must include black Americans, since nothing in the document says otherwise. “Neither in the preamble nor in the body of the Constitution is there a single mention of the term slave or slave holder,” Douglass explained in an 1857 address. “‘We the people’—not we, the white people, not we, the citizens or the legal voters—not we, the privileged class and excluding all other classes but we, the people.”

The anti-slavery constitutionalists emphasized a longstanding legal principle, holding that all laws that restrict natural rights must be interpreted as narrowly as possible, and that any time the meaning of a law is unclear, courts should interpret it in a way that will maximize freedom. These rules, combined with the broad purposes mentioned in the preamble—“to secure the blessings of liberty” and “ensure domestic tranquility”—meant the Constitution should be understood whenever possible as limiting slavery.

In addition, several clauses seem directly contrary to slavery—the prohibition on bills of attainder, for instance, of which slavery is arguably one type, or the Fifth Amendment’s promise that no person shall be deprived of liberty without due process of law. Other amendments guarantee fair trials and prohibit arbitrary seizures of persons or property. Given that slavery conflicted with these protections for freedom, the anti-slavery constitutionalists argued that the burden of proof was on defenders of slavery to show some foundation in the law for a practice that took freedom from people who had committed no crime. Absent some explicit justification for slavery in the Constitution, they believed that courts should at least presume against its legality.

Not only was slavery not expressly protected by the Constitution, Smith and his allies believed it was implicitly prohibited. They pointed to a sentence in Article 4 of the Constitution that prohibits states from interfering with the “privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” “Privileges and immunities” is a centuries-old legal term referring to personal freedoms. If black Americans were, indeed, citizens of the United States, then these words meant that states could have no power to deprive black American citizens of their liberty. Slavery’s defenders, of course, argued that slaves were not and could never be American citizens and therefore had no privileges or immunities. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney had even written an official memo taking this view while serving as Andrew Jackson’s attorney general in the 1830s. The Constitution’s authors, he wrote, had never contemplated black citizenship; they had intended to create a white nation. Thus, even black people who had never been slaves could not become American citizens.

But nothing in the Constitution addressed the question explicitly. Indeed, the document never defined the word “citizen,” which considerably complicated matters. Without such a definition, federal citizenship was assumed to spring automatically from citizenship in a state—individuals were federal citizens if and only if a state government recognized them as citizens. This created a problem because different states had different criteria for citizenship. Some drew no racial distinctions—a person of any race could be a citizen of Massachusetts, for instance, and consequently of the United States—but others, such as South Carolina, denied all black people recognition as citizens, whether born free or not. Thus, a person might be a U.S. citizen in some states but not in others—which was absurd, given that the “privileges and immunities” clause was written to bar states from making that type of distinction.

When South Carolina adopted its “Negro Seaman’s Act,” which mandated that black sailors on any ship pulling into one of the state’s ports be jailed until the ship departed, Massachusetts leaders argued that the act violated the “privileges and immunities” of black Massachusetts citizens who traveled on those ships. South Carolina ignored the complaints.

Smith and other anti-slavery thinkers argued that the privileges and immunities clause meant there were two separate types of citizenship—federal and state—and that federal citizenship took precedence, given that the Constitution is “the supreme law of the land.” Since black Americans were federal citizens— part of “We the People”—state laws to the contrary were null and void. It also meant slavery was unconstitutional, since it inevitably deprived black Americans of their federally guaranteed privileges and immunities.

True, the Constitution included provisions that obliquely protected slavery, including one that required the return of runaways and another that counted each slave as three-fifths of a person when allocating Congressional representatives. But even these provisions had innocent explanations, according to the anti-slavery theorists. The so-called fugitive slave clause—which actually uses the term “person[s] held to service,” not “slaves”—really applied to indentured servants and runaway apprentices, they said, and while the three-fifths clause recognized the existence of slavery, they pointed out that it gave slavery no legal protection.

On the contrary, it rewarded states with more congressional representation if they freed their slaves. Not a word of the Constitution would have to be changed, Douglass observed, for Congress to eradicate slavery nationwide.

White southerners took the opposite position: not only was slavery constitutionally guaranteed, in their view, but there was no such thing as federal citizenship at all. Citizenship was solely a state matter. That, in turn, implied that states could even secede from the union, since, if there were no federal citizens, then the federal government could not be sovereign. Only the states were sovereign, and the federal Constitution was really just a treaty between them, akin to a league of independent nations.

This argument ignored the fact that the Constitution had been written for the very purpose of eliminating the treaty-style system that prevailed under the Articles of Confederation, and that the Constitution explicitly refers to federal citizenship, while using only the word “inhabitant”—not citizen—when referring to state residency. The Constitution also gives Congress power to pass naturalization laws, which would make no sense unless federal citizenship was separate from, and superior to, state law.

These disputes over the constitutional status of slavery, which began in earnest in the 1830s, reached their climax in 1857 when Chief Justice Taney announced his ruling in the Dred Scott case: black Americans, even if they were not slaves, could never be citizens. Two years later, the State Department denied Douglass a passport on the grounds that he was not a citizen. Not until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868 did the Constitution define federal citizenship and expressly protect federal rights against state interference.

That achievement came about only through the leadership of anti-slavery constitutionalists like Smith and Douglass, who, when the Civil War ended, seized the brief window of opportunity to amend the Constitution in a way that ensured their understanding of the document would be forever enshrined in the nation’s highest law.

While Douglass was studying these constitutional arguments in the 1850s, he was also coming to reject Garrison’s pacifism. Alongside his own experience, particularly his fight with Covey, Douglass was inspired by the story of the rebellion a decade earlier aboard the slave ship Creole, led by a Virginian slave aptly named Madison Washington. Less well known than the Amistad uprising, the Creole mutiny struck Douglass as a real-life adventure of the liberty struggle. He was not the only one; it inspired Herman Melville’s story Benito Cereno in 1855. But in 1852, Douglass published his own novella based on it, entitled The Heroic Slave, regarded as one of the first works of fiction ever published by a black American author. Another inspiration was the 1851 “Jerry Rescue,” in which a group of abolitionists led by Gerrit Smith helped a fugitive slave named William “Jerry” McHenry escape to freedom. Smith, Douglass gushed, had raised abolitionism to “the Jerry level.”

But more even than these, what inspired Douglass’s thinking on the future of anti-slavery work was his meeting in 1847 with the militant abolitionist John Brown. A friend of Smith’s, Brown was living in North Elba, New York, about 300 miles northeast of Rochester, on land Smith had sold him. Brown was a shepherd, a failed businessman, and a religious fanatic who pledged his life to the destruction of slavery when, as a boy of 12, he witnessed a white man beating a slave with an iron shovel.

Like Douglass, he had started out as a Garrisonian pacifist, but came to reject that view and to embrace the idea that violence in a righteous cause could serve the Lord’s will. He must have been a man of intense charisma, for notwithstanding his Puritanical attitudes and Spartan habits, he inspired absolute devotion even in people who thought his religious beliefs silly. Douglass, anything but an Old Testament Christian, was nevertheless entranced. To the end of his life, he considered Brown among the “greatest heroes known to American fame.”

To order a copy of Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man, click here or here.